|

myOtaku.com

• Join Today!

My Pages

• Home

• Portfolio

• Guestbook

• Quiz Results

Contact Me

E-mail

• Click Here

OtakuBoards

• SomeGuy

Vitals

Birthday

• 1983-08-05

Gender

•

Male

Location

• Vancouver, BC

Member Since

• 2003-08-02

Occupation

• Writer; Part-Time Hero

Real Name

• James

Personal

Achievements

• Visiting eight different myO friends in person thus far

Anime Fan Since

• Winter 2001

Favorite Anime

• Neon Genesis Evangelion, .hack//SIGN, Naruto, Bleach, Beck, Peacemaker Kurogane, Ranma 1/2 (the guilty pleasure)

Goals

• Visit the myO friends I've missed thus far; complete a cosplay from 300

Hobbies

• Writing, Gaming, Kung Fu, Movies, Acting somewhat strange in general

Talents

• Can recognise most quotes from almost any movie/show on first listen; Can recite the entire 12 days of Christmas by memory

|

|

|

Thursday, November 9, 2006

Battle of Shanghai, August - November 1937

There's times when the futility of war doesn't matter to people. Even when they know they will lose a fight, they will still fight it. Call it pride, call it courage, call it hubris . . . . . even when you look at the larger of a picture of a situation, any simple explanation automatically gets complicated as well. The next historical moment I present has a lot of all of this, and whether my family's background has anything to do with it or not, well . . . I was very glad to have done a little research on this subject.

The Second Sino-Japanese War which went on to become part of the larger Second World War in 1941 officially started with "serious" warfare in 1937. For years prior to that, though, China and Japan had several battles downplayed and referred to as "incidents" among other things. These incidents included the annexation of Manchuria, territories around the Great Wall, Beijing (which I have written about before) . . . Japan was occupying China one piece at a time. No one was declaring all-out war, though; Japan didn't want to get drawn into World War II proper (and in turn have to fight Russia or the other western powers), and China didn't want to lose the supplies and resources it was getting from foreign aid protected by neutrality. Nevertheless, the two nations played their cat and mouse game; the Chinese trained "police officers" in military strategies, while the Japanese had "reinforced" factories and warehouses in Shanghai from past trading ventures. The two powers just barely skirting around the issue, and killing each other when opportunity presented itself . . . y'know, covered in pretext and stuff.

So how about this pretext: called the "Oyama Incident", a Japanese lieutenant tried to illegally enter a Shanghai airport and was shot and killed. Well, the Japanese government apologised for the incident (it WAS an illegal intrusion), but still demanded that the Chinese defenses and forces around Shanghai come down because of it - after all, the shooting of a Japanese officer was an embarassment and a humiliation. I think it goes without saying that China wasn't especially keen on this idea - they had been fighting the Japanese in Northern China for a long time already, be it official war or not.

Shanghai was already considered by the world to be THE Chinese city in China, where anything going in or coming out passed through. There were other factors as well: Shanghai was China's largest industrial city, and all the machinery needed to be pulled further into the interior. It was also a port that looked right out towards the Japanese navy in the sea to the east. See, at this point the Sino-Japanese conflict had been a mostly North to South fight, with the Japanese moving southwards from Northern China. If the Japanese fought south and went PAST Shanghai, Shanghai would be cut off without a fight and anyone in it would either be forced into the sea or lost in the city. Space for time . . . the Chinese forced a fight in and around China's most important city . . .

On August 13th, the two armies clashed in Shanghai's dense downtown areas. China's best trained fighters - trained by the German army, ironically enough (they even wore the same style of helmet!) - held the ground the best and headed the attacks of several Japanese positions in an attempt to drive them into the sea. The next day, the Chinese airforce started dropping its bombs on Japanese positions. Heavy Japanese defenses and a lack of Chinese heavy weapons to counter these defenses meant a heavy, heavy toll on the Chinese. To compensate, the Chinese would often fight "around" a target and cut it off, doing this successfully many times; the Japanese had technology like armoured tanks to compensate for that. By the end of this "first phase" of The Battle of Shanghai, all of China's best troops were wiped out. On August 22nd alone, the Chinese 36th Division lost 90 officers and 1000 troops.

August 23nd marked the beginning of the "second phase" of the battle, when Japanese troops from the sea landed amphibiously on the beaches along Shanghai and spread the battlefront from just inside downtown Shanghai to more of the city and outlying areas. Landing in waves after fierce shore bombardment (when Chinese soldiers, armed with light weapons, died by the battalion), they took the outlying villages quickly. Oftentimes they would take it in the day and Chinese counter-attacks would take it back. Ultimately, the Japanese controlled the shores. Fighting like this continued for two weeks until the Japanese surrounded the vital village of Baoshan which was defended by one remaining Chinese battalion with orders to "fight to the death" - they followed their orders to the letter, save for one man who survived. By September 6th, Baoshan fell, and a similar commitment to holding Shanghai continued for the next three months . . .

And that's how the next three months of Shanghai went. The Japanese would attack, the Chinese would defend with stubborness and inevitable futility. The town of Luodian was nicknamed "the grinding mill of flesh and blood"; the town of Dachang was smashed to rubble. After 75 days straight of holding several positions, the Chinese knew they had no way of holding the city any longer and began pulling out their troops . . . well, almost all of them . . . . . some stayed behind so that it could be said that China was still battling for control of Shanghai. True, they still needed time to pull the heavy industry out of Shanghai and westward, but there was another reason . . .

Here's where the politics gets complicated . . . now, the Chinese Army . . . . . it was not modern, it was barely professional, and it didn't have much of anything that it didn't copy or receive from other countries. China knew that its only real chance to beat Japan was to receive western aid. To do that, they had to prove that Japan was worth fighting against - more specifically, they had to prove that China was worth saving. In this sense, the dogged insistence to drag out the fight in Shanghai was China's way to shout out to the world that it wasn't defenseless, or that it wasn't going to lie down while the Rising Sun Flag flew over them. As they fought, the Nine-Power Treaty conference was taking place in Brussels to determine what the west should do for China . . .

The "third phase" started October 27th, and was basically the end for Shanghai. The Chinese were bled dry, low on supplies and ammuntion, and the Japanese were landing more and more troops. They had to pull back to the Wufu line, which was the last stand of sorts before coming to Nanjing, China's capital . . . . . when they arrived at Wufu, however, the beaten forces found most defensive positions had already been abandoned and boarded up - they could not defend the line even if they tried. On November 26th, the Chinese forces officially surrendered; Shanghai had fallen and Nanjing was wide-open for six weeks of utter, unquestionable hell . . . . .

China was in bad shape. Her best troops were already wiped out, her landmark city had been captured, and it was likely to continue in this fashion. Western aid would still not even begin to come until after December 7th, 1941 when America and the other western powers officially declared war on Japan. Japan, meanwhile, continued steaming through the top of mainland China and began its push inwards . . .

There is no question, this was a Japanese victory and an utter Chinese defeat. Though they started out with strength in numbers, they had poor equipment with which to arm those numbers . . . of an original strength off 600,000 men, Shanghai alone took out 200,000 or more. Japanese strength started at half that number and was reduced by 70,000. These, of course, do not count the tens of thousands of civilian deaths during the Japanese bombing campaigns earlier in the battle.

So why fight this battle at all if it was doomed from the start? Again, it was space for time; they needed to relocate the Chinese industrial engine. They also needed to switch the direction of the fighting from north-south to east-west; an eastern attacker meant the defenders could still retreat westward if they had to instead of just being cut off. Perhaps most importantly, though, it unified the Chinese people somewhat. Only a few years before the Japanese started their "incidents", the Chinese were fighting civil wars amongst themselves. This battle marked a point when warlords and major governments finally started getting their act together. This was a resolve China had to gain now if they were going to survive the next 8 bloody years of war . . .

The Japanese boasted that they would take Shanghai in 3 days, and China in 3 months. China made them fight for the city for over 3 months . . . . . as horrible as war is, it's hard to say that all that loss of life in Shanghai was for nothing.

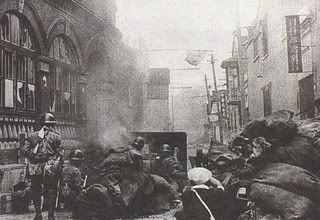

(Chinese machinegun nest in Shanghai)

(Japanese artillery set up in downtown Shanghai)

Comments

(2)

« Home |

|